![]() Triple conjunctions

Triple conjunctions ![]() Planetary conjunctions

Planetary conjunctions ![]() Lunar conjunctions

Lunar conjunctions ![]() Occultations

Occultations

![]()

![]() Triple conjunctions

Triple conjunctions ![]() Planetary conjunctions

Planetary conjunctions ![]() Lunar conjunctions

Lunar conjunctions ![]() Occultations

Occultations

![]()

A conjunction is the name given to occasions when two or more heavenly bodies come close to one-another in the sky. They are never physically close, of course - conjunctions are simply a "line-of-sight" effect when objects just happen to be in the same area of sky as seen from Earth. Planetary conjunctions are not that uncommon, as all the planets except Pluto orbit the Sun in more-or-less the same plane and hence appear in the same small strip of sky as seen from the Earth. An approximate calculation of how often a given pair of planets should come close together in the sky can be made from their orbital periods but this simple picture is complicated by the fact that the Earth is moving as well, which will change the exact time at which the line-of-sight is established and by an amount that will vary according to the particular circumstances of each conjunction. Experimentation with my astronomical program seemed the best answer here, which gave the (averaged) results below for the planets further away from the Sun than the Earth:-

| Mars-Jupiter: | 2yrs 83days | Mars-Saturn: | 2yrs 9days | Jupiter-Saturn: | 19yrs 83/4months |

The main interest in conjunctions is how close the planets get and how many are involved in a given conjunction. The conjunction between Mercury and Venus described in the "Mercury pictures" page was a very close one - only 41/2 minutes of arc, in fact - or less than one-sixth of the diameter of the full Moon (which is about 1/2 degree, or 30 minutes of arc). Anything within a couple of degrees will be notable but there's really no definition of how close an approach must be to be called a conjunction. Clearly the most common conjunction will involve just two planets but triples do also occur reasonably often - conjunctions involving more than three are unusual though. Incidentally, while a coming-together of two planets is correctly called a conjunction, an event involving three is not called a triple conjunction! This term is reserved for occasions when two planets come close three times in a short period (yes, it can happen but no, I'm not going to elaborate). The correct term for "multiple conjunctions" is a grouping or massing. I shall continue to use the "wrong" term below though!

Remarkably, all possible conjunctions (with the exception of Jupiter-Saturn) happened in the space of just 13 months from February 2008 to March 2009, and there were six conjunctions in just ten weeks from April to May 2011 (very low at dawn, however).

The most recent triple (which I define as all three having separations of less than 3deg) was on 10th January 2021, involving Mercury, Jupiter & Saturn when the separations were M->S 13/4 deg, M->J 2 deg and J->S 21/4 deg. Before that, Mercury, Venus & Jupiter came together on the evening of 26th May 2013, when the maximum separation was only 21/2 deg, and the "massing" of 26th October 2015 between Venus, Mars & Jupiter was a very near miss at 31/2 deg. The next true triple will not be until dawn on 20th January 2026, when Mars, Saturn & Mercury will be nearly in a straight line separated by 11/5 deg (Ma->S) and just 3/5 deg (S->Me), but very close to the horizon. There's not a naked-eye "quad" before 2033, and a full set of all five close to each other will not occur until 8th September 2040! Worth waiting for, as it will also include a 2-day old crescent Moon, but very low down in the evening sky as seen from the UK.

Conjunctions between the major planets are not, of course, the only type of conjunction. Planets can come into conjunction with stars; the Moon can come into conjunction with planets and stars, and the asteroids [small bodies orbiting between Mars and Jupiter] can have conjunctions of their own. Conjunctions with stars don't tend to be particularly dramatic events unless the stars are quite bright and of course lunar conjunctions can be overwhelmed by the great brightness of the Moon: conjunctions with the crescent Moon can be quite spectacular though (see below for a conjunction with Venus). Lunar conjunctions can be useful for finding planets further out than Saturn, however, as the close proximity makes the identification of the correct "dot" much easier. See my gallery of pictures of Uranus for an example of this.

Conjunctions involving asteroids and the outer planets are relatively uncommon, as their orbital periods are quite long (3.6 to 4.6yrs for the largest ones) and their orbits tend to be inclined to the plane of the solar system so they often travel outside the band of sky traversed by the planets: there was one between Vesta and Jupiter in August 2007 though (see my Asteroids page for further information) and an extremely close one (1/5deg) between Vesta and Venus on 22nd June 2013. Because of their similar orbital periods and inclined orbits, conjunctions between two (large) asteroids are among the rarest of planetary phenomena: just three events in the 21st Century, including an exceedingly close meeting between Vesta and Ceres during the evening of 7th July 2014 - just 1/6deg (10 arc-minutes, or 1/3 of the apparent width of the Moon). Again, see my Asteroids page for further information. Conjunctions with Mercury and Venus happen approximately annually (as with "major" planets) but, as these will be near the Sun, in practice they are very difficult to observe.

I haven't listed upcoming conjunctions on this page because, as they happen reasonably frequently, I would have to keep on updating the page. Instead, I have listed them (together with other notable events) on the "What's coming up" page linked from the My Astrophotographs index page.

The most extreme conjunction is when two objects come so close that their discs overlap: this is called an occultation. Strictly, it is only an occultation if the "foreground" object is (apparently) bigger then the "background" object: if the reverse is true the event is called a transit. One could thus say that an annular eclipse is a transit of the Moon across the Sun and a total eclipse is an occultation of the Sun by the Moon!

Occultations of one planet by another are exceedingly rare [last one was in 1818, next is not until 2065!!]. Occultations by the Moon happen more frequently though as the disc of Moon is (clearly!) very much bigger than that of any planet. And although the Sun can of course occult planets, because of its extreme brightness the only "occultation-type" events sensibly visible are eclipses & transits by the inner planets Mercury and Venus: see my pages on eclipses and transits for more information on these types of events. Note though that an "occultation" of a planet by the Sun is actually caused by the planet moving behind the Sun as seen from Earth, as a result of the relative motion of Earth and planet, rather than by the planet being slowly covered by the Sun as a result of the Sun's motion. This type of "occultation" thus has a particular name - it is known as Superior Conjunction.

Occultations of stars by the Moon and planets are reasonably common (as there are lots of stars!) so I don't usually bother to observe them. The exception is occultations by asteroids - these are much less frequent, as asteroids show a very small disc and so the chance of them occulting anything of a reasonable brightness is much reduced.

Just as the planets in the solar system can be involved in occultations and transits, so can the satellites of the larger planets, acting as sort of "mini solar systems". In practice, only those involving the Galilean moons of Jupiter are easily observable but they offer all types of phenomena: eclipses; transits across the disc of Jupiter; occultations behind it, and occultations & transits of one moon by another. See my section on Jupiter for more information.

As mentioned above, although not exactly rare, lunar occultations are relatively unusual. The reasons for this are rather complex so I have moved the discussion onto an additional page to avoid a "pictures" page turning into a theory one. Click here to read it.

Note that these are the GMT times of the beginning of the occultation.

| Moon-Mercury: | 3rd Nov 2040, 5:58am | Moon-Venus: | 10th Jan 2032, 6:30am | ||

| Moon-Mars: | Nothing this side of 2040! | Moon-Jupiter: | 21st Nov 2034, 11:23pm | ||

| Moon-Saturn: | 9th December 2036, 5:52am | ||||

![]()

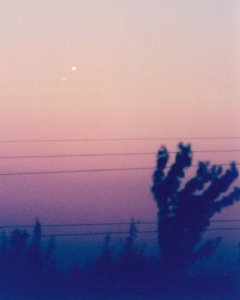

So, onto some pictures of actual events. The first is of the Mercury-Venus conjunction of 27th June 2005 mentioned on the "Mercury" photos page, taken using an 840mm lens on a 35mm film camera:-

| Here we see Mercury and Venus in the rapidly fading twilight of a rosy sunset. And no, that is not a cactus at bottom right - I know we had a dry June but that's just ridiculous! The grey disc on the right represents the full Moon at the same scale: the separation was just less than 5 arc-minutes (1/12 degree). |  |

| The Venus-Mercury conjunction was actually a triple conjunction a few days earlier but, inevitably, it was cloudy here around that time so here's a picture taken from the Internet, at the same scale as those below, showing Saturn, Venus & Mercury on 25th June. The maximum separation (Saturn-Mercury) is 12/3 degrees. | |

And here's lots more conjunctions, taken with a digital camera: note that the scale is about one third that of the Mercury-Venus picture above! The grey discs again show the size of a full Moon for comparison. | ||

|  | |

| Venus and Jupiter, captured by Sandra in the evening dusk at Laxfield on 2nd September 2005. The separation is 11/2 degrees. | Mars and Saturn on 22nd June 2006, separated by 21/3 degrees. They were much closer a few days earlier (just over half a degree) but, you've guessed it, it was cloudy for several days here!! | |

|  |  |

| In August 2006 there was a double conjunction at dawn involving Venus and Mercury & Saturn. Although the three did line up (twice, in fact), one couldn't really call these triple conjunctions as the separations were all over 4degrees. Apart from which, it was cloudy (again) so I didn't see them anyway! The pictures above show (at the same scale as before) the minimum approach of Mercury to Venus on the 10th (21/4 deg.) and the very close approach of Venus to Saturn on the 27th (just 13 arc-minutes). Both pictures were taken at 5am (!), showing how much Venus had moved between the events - compare against the same tree on the right. | ||

I tried to see the close grouping of Jupiter, Mercury and Mars on 10th/11th December 2006 but, although I spotted Jupiter and Mercury in the binoculars on the 10th, I didn't notice that, because it was so cold that morning, the lens of the camera had slightly frosted up! Result - no usable pictures. It was then totally cloudy and rainy on the 11th so I tried again on the 12th, to be rewarded with a perfect dawn. We thus have, from the left, Mercury Jupiter and Mars: separations are 2 degrees and just under 1 degree respectively. Would have been 3/4 degree the morning before but hey, at least I saw it! |  | |

| After being close together in the morning sky in August 2006, by July 2007 Saturn had passed through opposition and was heading back towards the Sun again and Venus had also "swapped sides", as it were, being now a brilliant evening star. The two were thus able to come back into conjunction but at sunset this time. Despite a really terrible period of bad weather I was fortunate enough to be able to catch them at minimum separation (3/4 degree) late in the evening of the 1st.  | |

The period February 2008 to March 2009 was quite a special one because all possible conjunctions (with the exception of Jupiter-Saturn) happened during this time. Here's the first event, Venus above Jupiter just before dawn on 1st February - the separation is 2/3 degree. These two planets give us the brightest pairings so the view was quite spectacular: until the cloud closed in, that is! |  | |

| This game is called "spot the planet". The planet in question is a very bright Venus, so it can't be a problem, can it? Well yes it can, as a rising Sun and even the thinnest cloud at this elevation above the horizon (just 31/2deg) conspire to blot most things out. When you give up, hover the mouse pointer over the picture to see a heavily contrast-enhanced version of the image, just to prove it really was there! I've included this image, of the Venus-Mercury conjunction at the end of February 2008, to show how difficult it can be to observe near to the horizon and close to the Sun: and no, I haven't been able to find Mercury either! It should have been above and to the right of Venus but at fourty-five times less bright than Venus at the time I don't think I had much chance of capturing it under these conditions. | |

I had been watching Mars approach ever closer to Saturn during the early summer of 2008 and here they are at their closest, late in the evening of 10th July - the separation is 2/3 degree, with Saturn above Mars. This is the closest conjunction between these two planets until 2022.  |  | |

Having met in the morning skies in February 2008, Venus and Jupiter came together again in the evening during November and December. This was made even more spectacular by the intervention of the Moon, an event dubbed the "Great Conjunction". Read all about it by clicking here.

| After its encounter with Jupiter and the Moon early in December, Venus carried on to a conjunction with Neptune at the end of the month. The minimum separation, here on the 27th, was 11/3 degree: Neptune is the middle one of the line of three to top right. The brightest star (bottom left) is Nashira, in Capricorn, but none of the others is distinctive enough to have a name (which goes to show how faint Neptune was! Magnitude 8, in fact). [Note that this image is not at the same scale as the others on this page]. I wouldn't normally try to capture conjunctions with Neptune (or indeed Uranus) as they are not particularly photogenic but thought I would on this occasion as, just after the coming-together of the two brightest planets, here we have the conjunction of the brightest and the dimmest. Using Venus as my guide, I was actually able to capture Neptune on four out of five consecutive nights so have included a fuller description in the "Outer Planets" page - click here to read about it. | |

Jupiter also had a second conjunction around the turn of the year, with Mercury, always a difficult target to spot. There was just enough cloud on the horizon to prevent me seeing Mercury on the day of closest approach (31st December) and the next two days were competely cloudy. Mercury moves across the sky very quickly though so by 2nd January it had risen quite a lot higher in the sky, thus making it easier to see, but further from Jupiter - the separation by this time (here shown to correct scale) was 21/2 degrees, with Mercury to the left of Jupiter. |   | |

| While checking star maps for the track of the ISS in mid-July 2009, I noticed that Jupiter and Neptune were very close in the sky, which gave me another opportunity to capture the elusive outermost planet. This image [actually a "stack" of four] was taken just before midnight on 12th July when the two were just past the point of closest approach, but even so the separation was only a fraction over 1/2 degree. Jupiter is (obviously!) to the bottom of the frame, with its satellites Ganymede, Europa and Callisto also visible, and Neptune is to top left. The only other object visible is the 5th magnitude star, Mu Capricorni. As with the Venus-Neptune conjunction above, this image is not at the same scale as the others on this page - the increased magnification shows Neptune's distinctive light blue colour quite well. The image also again shows how dim Neptune is. Although seeming bright here, the star would be only just visible to the naked eye yet Neptune is 13 times fainter still. Just to prove it was Neptune, I took some further images a couple of days later - click here to see the results. | |

After a rather barren spell for conjunctions during the first half of 2010, Mars finally caught Saturn at the end of July. As an added bonus, Venus was nearby to produce this very photogenic result in the evening twilight of the 31st. The separation between Mars and Saturn was 13/4 deg, and between both Mars & Saturn and Venus it was 73/4 degrees (hence the larger image, necessary to maintain the "standard scale"). |  |  |

| Early morning is not really my time of day and so I had to wait literally years for another evening conjunction which was actually visible (cloud can be intensely frustrating!). Venus and Mars finally obliged on the evenings of 21st & 22nd Feb. 2015. The separation was just 1/2 deg, as can be seen from the size of the nearby thin crescent Moon - all to "standard scale" - which joined in on the 21st. The close-up below (at 8-times standard scale) shows the dramatic colour difference between the two planets, as the vivid orange-red of Mars contrasts with the brilliant white of Venus (and while the apparent size of Venus was almost three times that of Mars, the difference is exaggerated here by a degree of over-exposure because Venus was 5.2 magnitudes - or fully 120 times! - brighter than Mars).  | |

| Venus obliged again during 2015, when it had an equally close encounter with Jupiter on 30th June & 1st July. The separation was actually a little less than in February on the 30th, just 1/3 deg. I was able to get an excellent view of it, as a particularly hot period had produced some clear skies, but was unfortunately unable to take any 'photos as I was at an orchestral rehearsal at the time! The weather then became cloudy on the 1st so I assumed I had lost my chance. I went out with the camera anyway, and was astonished to see an orange "star" peeping through the tree-line on my western horizon. Not a star of course, or even Mars, but Venus so low down that its brilliant white had been reddened by the twilight. I could see absolutely nothing through the viewfinder but popped off some shots anyway and was delighted to find I had captured the conjunction very nicely! (top left). I thus ran to where I had a clearer view of the horizon and took a few more shots before both planets finally set just a few minutes later, as shown to bottom left. The images below were taken the day after, when the separation was already up to almost 1 deg. The close-up (at 4-times standard scale) shows both planets reddened by their low elevation. The difference in brightness is 2.7 magnitudes or a factor of 12, very much less than for Venus and Mars above. By coincidence, their apparent sizes were exactly equal, 32 arc-seconds, though as above their "photographic size" is affected by over-exposure.   | |

2016 opened with an extremely close conjunction between Venus and Saturn. Unfortunately, this was in the dawn skies and during a period of very variable weather so I didn't expect to be able to see it. However, I had to be up reasonably early that day (9th January) so took my camera to bed with me just in case. When the alarm went off at 7:30am I looked out of the window and - what do you know? - there was Venus glittering in a small patch of clear sky! I grabbed my camera and fired off a few quick shots, one of which captured both planets (but only just!). You can barely see Saturn on the original image, because it was relatively dim (just mag. 0.53) and the sky was quite bright, and it didn't survive the re-sizing required to derive the smaller image. However, if you click or tap on the picture to overlay a (slightly scaled) small section of the original version Saturn reveals itself - yes, it's that slight smudge to the right of Venus! The overlay is at 5-times standard size, showing how close the conjunction was - a mere 1/6 of a degree in fact. |   | |

Following another period of morning conjunctions, I just happened to notice that Mars and Neptune would be extremely close together on 7th December 2018. In this image Neptune is the blue-grey "star" (magnitude 7.9) to the 5 o'clock position of Mars - the brighter star to 1 o'clock is 81 Aquarii (magnitude 6.2). The minimum separation between the planets was a mere 2.4 arc-minutes but this was when the sky was not fully dark. By the time I took this shot the motion of Mars had widened it to just less than 10 arc-minutes (hence the larger "moon disc", necessary to maintain the standard comparison). |   | |

While the "coming together" of Venus, Mars and Saturn in 2010 pictured above cannot really be called a triple conjunction (as Venus is too far away), the meeting of Mercury, Venus and Jupiter in May 2013 definitely could. This was the best opportunity to view a triple since 2006 (shown above) and until past 2036 (!), so I had been looking forward to it for some time. Read how I got on by clicking here.

I stated in the introduction to this page that unless the separation between any two of the planets involved is no more than 3 degrees, I did not regard the grouping as a conjunction. On this basis, the alignment of Venus, Mars and Jupiter in October 2015 was not a conjunction, as even at its tightest the separations were 31/2 deg. However, it was publicised quite heavily on the BBC News, and it was "almost there", so I thought I'd better try to capture it. The major downside was that it was a "morning" conjunction - not my best time! Read whether I managed to get up in time by clicking here.

Historically, a conjunction of the major planets Jupiter and Saturn is referred to as a Great Conjunction as it is the coming together of the two largest planets. That in late in 2020 was the best opportunity to view a Great Conjunction since 1226 (!!), so was definitely not one to be missed. Read whether I managed to see the sight of a lifetime by clicking here.

As mentioned at the top of this page, for several planets to come close together in the sky is quite rare. However, if we simply ask that several be visible in the night sky at the same time while not necessarily being close together (an event which has the unofficial name of a "Parade"), this will happen considerably more often. Have a look at one which occurred in February 2025, and read about further Parades upcoming, by clicking here.

![]()

The term "conjunction" usually refers to planets, but of course the Moon can be involved too. Here are some dramatic examples:-

| On the left we have a lovely conjunction of Venus and a very thin crescent Moon on the evening of 20th January 2007. The "centre-to-centre" separation is about 12/3degrees, with the Moon barely 40hrs old. If you look carefully you can just see the full disc of the Moon faintly illuminated by "Earthshine": light reflected from the Earth back to the Moon. On the right, the Moon is even "younger" - 32hrs - and the Earthshine is much more obvious as the image was taken later into the twilight, on 6th May 2008. The planet on this occasion is Mercury, with the separation being a fraction over 2deg. |  |

And a "triple conjunction", of sorts! Here we have Mercury below the Moon on 26th April 2009 with the Pleiades above it - taken later in the evening than both those above, Earthshine is very noticeable. The Moon was just 41hrs old, with the separation from Mercury being 2 degrees and from the Pleiades 11/3 degrees. |

All the conjunctions above have been either at sunrise or sunset. To some extent this is just chance, because except for Mercury (and to a lesser extent Venus) all the planets can also be involved in conjunctions during the hours of darkness - the images are not so photogenic though, due to the lack of foreground! | |

|  |

Here we have the Moon again, in very close conjunction with Saturn at 11pm on 2nd February 2007. The centre-to-centre separation is less than 1/2degree: "edge-to-edge" it is only 12 arc minutes. The Moon is just past full - about 15hrs in fact. On the left the two are at the same scale as the images above - note that the grey discs really are the size of the full Moon, as claimed! On the right is a larger-scale image showing how the conjunction looked through binoculars - the great brightness of the Moon meant it was impossible to photograph it and Saturn at the same exposure so this is a montage of two images taken separately. The Moon actually occulted Saturn the next month - see below. | |

| |

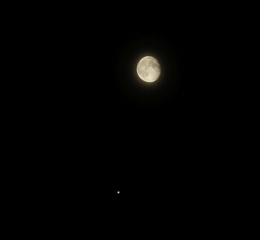

In this image (which is at standard scale), the Full Moon is close to Saturn at top left and Jupiter at top right, at 00:32am on 6th July 2020. The centre-to-centre separation to Jupiter is about 3 degrees and to Saturn it's about 61/4 so the event cannot be called a conjunction, but it was a dramatic sight nonetheless. As with the Saturn conjunction above, it is actually a montage due to the great brightness of the Moon | |

Events such as that above were not really possible after 2020 as Jupiter, in its more rapid orbit, quickly moved away from Saturn in the sky. I noticed however that there would be an interesting "coming together" between the Moon and Saturn in late August 2023, as Saturn would be at opposition on the 28th and on the 30th the Moon would be not only at perigee but also a Blue Moon (the second Full Moon in a month). Also, the Moon would be even closer to Jupiter in early October when just a few days after being again both Full and near perigee. Even better, Jupiter itself would be just a month before opposition and therefore very bright. | |

|  |

And here we have my pictures of these events, at standard scale - Saturn on the left and Jupiter on the right. Again, these are montages due to the great difference in brightness between the planets and the Moon. The Moon-Saturn separation was 33/4 degrees and that between the Moon and Jupiter just 21/2 degrees so although both approaches were close neither event can really be called a conjunction. | |

| |

During the evening when I took the images featuring Jupiter the sky was initially overcast but then partially cleared to leave just misty high cloud. This did not affect the close-up photography too much but resulted in the Moon being surrounded by a beautiful halo - a "22 degree halo" in technical terms, as this is the angular distance the halo is away from the Moon. I was keen to capture this phenomenon because, as the Moon was quite low in the sky, I thought it would make a good image with the halo shown against the tree-tops. This image is the result. If you look carefully, you can see that Jupiter was so bright that it is still visible below the Moon despite the Moon being very bright and also enlarged due to the long exposure necessary to capture the halo. Click or tap on the image to enlarge the section round the Moon so as to see Jupiter better. | |

|

| And finally, for the moment, not really a lunar "conjunction" as the separations are way too large (and therefore it's not at standard scale) but a very photogenic sight captured in the early evening of 2nd January 2017. The Moon is (obviously!) in the centre, with Mars 7 degrees away to its upper left and Venus 41/2 degrees to its bottom right. The "foreground" is Laxfield church. Remarkably, the dog walkers who passed me while I was taking pictures didn't even seem to have noticed the sight spread out before them! Further interesting line-ups occurred one and two months later. Click here to check out the one I spotted in Feb/March. |

![]()

Occultations don't happen very frequently so I was keen to capture that of Saturn by the Moon on 2nd March 2007. The weather had been very variable in the week previous but luckily cleared just on the evening of the occulation. The downside was that the event occured at 2:35am! Ah well, are we dedicated or not? Despite the best planning, however, things can go wrong and indeed they did. The worst near-disaster was when the web-cam slid partly out of the eyepiece tube thus ruining focus and resulting in fuzzy images. At first I put this down to bad atmospheric conditions and didn't deduce the real answer until after the "inward" half of the occultation was over. The images were, however, good enough for me to be able to reconstruct what I would have seen had I noticed the problem sooner.

Fortunately however, occultations have two parts and so I was ready for the "outward" half. This was also missed as well though, as I was initially looking at the wrong section of the Moon's limb! I realised just in the nick of time, so was able to get a pretty good series of Saturn emerging from behind the Moon. Exposure was something of a problem, as the Moon is so much brighter than the planet, so I concentrated on getting things right for Saturn and took a few shots of just the Moon later so I could combine the two digitally to give an accurate "visual" representation.

| On the left we have Saturn "flying" above the Moon's cratered surface some minutes after having emerged from behind its limb. The dark area to the top is Mare Nectaris, with bright spots on each side of the crater Stevinus particularly prominent at right-centre. The animations below show Saturn disappearing and then re-appearing after the occultation: each sequence represents about 5mins in real-time. Note that in reality the Moon was actually moving in front of Saturn, not Saturn behind the Moon: showing it the latter way made it easier to align the frames of the animation though! | |||

| The prominent crater behind which Saturn is "disappearing" on the left is called Cabeus: note the sunlight glinting on the central peak. The feature to upper middle is a circular mountain range called Drygalski. On the right, the dark patches are part of Mare Australe, with the dark crater Oken to far right. |  | ||

My next opportunity to view a lunar occultation of Saturn was not until 2024. The weather forecast had been predicting clear skies at the relevant time for a few days so I was quite optimistic of a good result. Conditions were looking encouraging upon arrival just before dawn at my pre-surveyed observing site but unfortunately thin clouds started to drift up from the south just as the Moon was on the brink of obscuring Saturn and didn't really clear thereafter. I did get some images but it really wasn't the spectacle I was hoping to see. To find out what I did manage to capture, and how I dealt with the images thereafter, click here.

The Moon's meeting with Mars in the early morning of Christmas Eve 2007 wasn't actually an occultation (i.e. the Moon did not cover any part of the disc of Mars) but was so close - just under 2minutes of arc - it was categorised as a "near miss" instead of a simple conjunction. The weather was most unhelpful here unfortunately, with complete cloud cover for a day or so beforehand, so I was not particularly hopeful. I got up at 3am anyway (yawn), and did manage to catch a few glimpses of the Moon through scudding broken cloud so thought it might be worth setting up the equipment. The main telescope plus webcam didn't prove to be usable though, as firstly the highly variable cloud caused the exposure to be all over the place and secondly my laptop (used to capture the images) chose this moment to shut down and refuse to turn on again!! Mr Murphy and his Law were having an early Christmas! I thus transferred to the digital camera at full magnification (800mm equivalent) which at least meant I could choose my moment to take a shot - the exposure was still guesswork though!

All this meant that very few images were usable - just three, in fact. Not particularly impressive, but better than nothing! By chance, these were at about the time of closest approach so at least I got something to show here. I have made them into an animation and a composite picture (in black&white for a clearer view). The first image was taken at 3:44am, then 3:50 and 3:55 - closest approach was 3:46am. As with the animations of Saturn above, it was really the Moon moving, not Mars, but I felt the animation looked better this way round.

|  |

I was hoping for better luck with an actual occultation in 2022 than I had with the "near miss" in 2007 and, just for once, my luck was in with almost perfect conditions, allowing me to take a good series of images. I processed these to show both the ingress and egress, and also made animations of each phase. This resulted in too much information to include here so I constructed a number of pages of information about the event which can be accessed here.

I wasn't too hopeful about capturing a daytime occultation but as the sky was clear I thought I might as well get the binoculars out to check what I could see. The view actually surprised me, so an almost last-minute decision to get the equipment out was made. To see what I managed to capture, click here.

I discovered quite by chance (just the the day before, in fact) that asteroid Metis would occult the magnitude 7.8 star HIP78193 (which sits between the constellations of Libra and Scorpius) in the early hours of 7th March 2014. Metis would be at magnitude 10.6 at that time, and so during the occultation the star would apparently disappear. Consultation of the visibility map and table of local circumstances given via the website of the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) indicated I could be close to the borderline between seeing an occultation and not, so I was keen to observe the event. However, this meant getting up at 2:45am (yawn!) and attempting to take pictures out of my bedroom window in order to get a line of sight!

| Having lined the camera up on the right part of the sky, I took a series of images from before the occultation was due to begin at my location until after it should have finished (spanning a few minutes either side of 03:08am). Conditions were not particularly good, so in order to improve the images I stacked several from before the start; from during the time the star was supposed to be occulted, and from after the occultation ended. Therefore, if an occultation actually took place I should have seen the star on the first and last stack, but not on the middle one. The image on the left is the "before" shot. The brightest star is Theta Librae (mag. 4.1) and the one well to its left is 49 Librae (mag. 5.5). HIP78193 is barely visible, but can be found by looking about a third of the way from 49 to Theta and then moving down by about the same amount. As a guide to relative brightness, the faint star pointed to by the pair at top left is exactly the same magnitude as HIP78193. Click or tap on the image to show firstly the "during" image and then the "after". It can be seen that HIP78193 is visible in both these images, with a visibility which remains comparable to the comparison star previously mentioned. I thus concluded that no significant decrease in brightness had taken place during the time the occultation was predicted to have been in progress. |

Given that no occultation seemed to have occurred, I checked the alignment of star and asteroid using the Solex astronomical calculation program written by Aldo Vitagliano. This showed that, as my observations indicated, Metis would indeed not have occulted the star as seen from my location - I was just to the north of the borderline, as I had thought. The diagram below (constructed from Solex data and set for the mid-point of the event) shows this nicely. The apparent diameter of Metis is given as 0.158 arc-sec and the offset between the objects is only a tenth of this distance - close, but no cigar!

Experimentation with Solex showed that there would just have been an occultation at latitude 51.95deg, about 24mls south of my location (at latitude 52.30deg). The southerly limit at the same longitude was 47.50deg, giving a range of 4.45 degrees of latitude or about 307mls. This is somewhat more than given by the IOTA local circumstances, which seems to be due to the different apparent diameters used - Solex quotes 0.158 arc-sec but the official figures state 0.127. Solex also shifts the range to the south somewhat, which is presumably due to the very slightly different orbital parameters used. A small difference here can have quite a large effect, though, and it was this shift that caused Solex to predict there would be no occultation at my location. Even if one went by the IOTA figures, where the northern limit was given as 52.40 deg, at best the occultation would have been a grazing one as seen from my location. I would not have been able to detect this, as the individual images were not good enough to provide accurate brightness information.

And that's how a "non-occultation" can be almost as interesting as an actual disappearance!