|  |

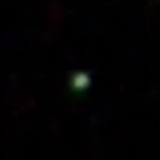

| Yes, that blue-green spot really is the planet in question! | A much expanded view shows it's not just a blank disc that I've invented or a star captured by accident (the faint lines are artefacts of the computer processing though). |

Uranus and, particularly, Neptune are difficult subjects to get images of because, being so far away, they are much fainter than the other planets. Though Uranus is nominally visible with the naked eye, in fact it is not easy to spot unless the sky is crystal clear and so really needs binoculars. Neptune is always a binocular object so is thus very hard to find in the first place and then tricky to capture. The problems are compounded when using the telescope (with its small field of view) as unless there is a reference object nearby it is almost impossible to know you've got the right target.

My first success with Uranus was really just an incidental finding when I was doing my series of Mars in 2003. I noticed Uranus was not far away in the sky and was amongst a particularly distinctive group of stars which would make it easier to find. I was able to track its motion amongst the stars for several days with binoculars and thus be sure that I'd got the right target when I looked at it with the telescope.

Uranus is so far away that even its giant size doesn't make much of an impact on the webcam sensor: just 7 pixels wide, in fact. The left-hand image is shown at the same scale as the other shots in this gallery to enable direct comparisons to be made. The original image was rather over-green due to colour-balance issues, so I've corrected it by reference to an actual picture of Uranus. The right-hand image is expanded by 8-times, just to show there is some structure to the blob: you'll have to take my word for it that the image is genuine! I could have included more but as they would have been rather boringly similar decided not to.

|  |

| Yes, that blue-green spot really is the planet in question! | A much expanded view shows it's not just a blank disc that I've invented or a star captured by accident (the faint lines are artefacts of the computer processing though). |

I was never quite sure whether just one shot actually counts as a "gallery", so I was keen to take advantage of a close conjunction between Uranus and Jupiter on 21st September 2010. This conjunction was particularly special as both planets were also at perihelion at the time and so were at their largest and brightest. This didn't make all that much difference to Uranus, as it's so far away anyway, but Jupiter was a great sight. See a little further down this page and also my "Jupiter" page for details of what I was able to capture!

Uranus was not only close to Jupiter (about 0.8 of a degree) but also almost exactly above it, so once I'd taken my images of Jupiter it was an easy matter to move the telescope up a little and thus home in on my second target for the night. Since my last attempt, I had become more experienced at selecting exposures correctly and so the resulting images were a lot better than in 2003. I didn't need to do so much image processing to "drag them out of the noise" and so the final result is much more like a planet than a blob!

|  |

The "as observed" image seems much the same as before but the 8-times expanded view shows it is at least circular this time! It also demonstrates the brightness fall-off towards the limb characteristic of gaseous planets. The small image is an averaged stack of eight individual frames, colour-balanced and contrast enhanced. To produce the large image, the small one was blurred a little (to reduce the effect of pixellation), re-sampled to eight times original size and re-balanced for contrast.

Between the two imaging sessions above I was very pleased to note that the Moon would come quite close to Uranus in the early hours of 2nd August 2007 thus giving me another opportunity to capture this elusive planet. It would not be easy though for, although I knew exactly where Uranus would be, the overpowering brightness of the Moon would make capturing an image an unpredictable business.

I tried to view the conjunction both through my telescope plus webcam and directly with the digital camera. The former didn't really work because its field of view is so small that even if you know where something is in theory it still doesn't mean you'll actually be able to find it in practice! There was no real problem with the digital camera, being simply a question of putting the Moon in the appropriate position in the frame and assuming Uranus would be there as well when the frame was examined later. I had gained some experience with faint objects when doing my series of the moons of Jupiter so was fairly confident of getting the exposure right - even if I didn't, the great advantage of a digital camera is that you can immediately see what you've got and thus try again if things haven't worked. As it turned out, my confidence was well founded in that I got several good shots (and a number of duds!) from which I have constructed the images below:-

|  |

| This shows a vastly over-exposed Moon at the top, with Uranus between two stars below - you might have to look carefully! The brighter star on the right is Phi Aquarii, that on the left 96 Aquarii. The image is the "average" of two shots taken close together (a process which brings out the important detail and reduces the background clutter). As you can see, I was quite lucky that the flare from the Moon just missed Uranus on this occasion. | This shot is also the average of two, as can be seen from the grey bits to left and right - the images didn't quite line up! Indeed, on one shot I missed Phi Aquarii altogether so it's sitting in the dark grey stripe to the right. More by luck than judgement, this image is actually the instant of least separation - just under 1deg centre to centre, so the distance from Uranus to the edge of the Moon (which has moved since the last image) is about 3/4deg. |

|  |

| And finally, just the objects of interest. The Moon has again moved since the above images and the sky has also shifted round as the Earth turns, hence the different orientation of the "spots". See if you can find Uranus and click on it! (hint - it's just above centre). You might even be able to persuade this to work with a touch screen, but hitting the right spot will be much more difficult! | Rather more art than science, this one! A somewhat fanciful montage to show what the scene might have looked like had it been possible to correctly expose both the Moon and the stars plus Uranus. |

When I was compiling my series of images of the asteroid Vesta in late August 2007, I realised that the digital camera would be sensitive enough to capture good images of Uranus without too much problem and also probably Neptune under favourable conditions. By sheer coincidence, Uranus was at its nearest to the Earth for that year in mid-September and at the same time Neptune was only just past opposition itself, so they would both be about as bright as they could get: magnitude 5.7 and 7.8 respectively (To find out about the magnitude scale, click here). Several clear moonless nights, a couple of which were crystal clear, gave me the opportunity to put theory into practice.

Having found the planets with binoculars (which was in fact the first time I had ever seen Neptune!) I was able to home in on their locations in the sky by steadily increasing the effective magnification of the camera lens while taking test shots to see how close I was. Uranus was soon captured with no problem but Neptune was considerably more difficult, being seven times as faint (and thus quite tricky to see even in binoculars) - in fact I could only get reasonable pictures on the two particularly clear nights. The usual stacking and image processing techniques then brought out the detail in the shots.

| The first image might be called "spot the planet" and shows the difficulty of determining which star isn't a star. From the collection of blobs on display here, how can you tell which is which? By reference to a star chart is the obvious answer but when viewed through a telescope they all look very similar - proving you've got the right one in view is thus a considerable problem. Not so hard with the camera though (as long as you can recognise the patterns you're seeing, of course!). Uranus is actually the middle one of the three in the top right quadrant. The brightest of the three is is the same Phi Aquarii we saw in the pictures with the Moon above and 96 Aquarii is to its "10 o'clock" position: note how far Uranus has moved in five weeks. |

| Now we've zoomed in to show just those three objects. The orange star to bottom left is Phi Aquarii (magnitude 4.2) but that to top right is insufficiently bright to merit a name in the constellation of Aquarius. The distance between them is fractionally under 1degree (twice the width of the full Moon). The third, greenish, object is of course Uranus. |  |

| |

| Over the course of the next few days, Uranus moves slowly to the right. These images were taken on 11th, 13th, 14th and 15th September (it was cloudy on the 12th!). | |

| By combining the above images the planet's progress from 10th to 15th September is well illustrated - it is also more obvious that one day's observation is missing. The astute reader will perhaps notice that Uranus is going "the wrong way" - planets' true orbital motion will cause them to move from right to left as seen from the northern hemisphere of the Earth. This reverse motion is a purely geometrical effect (known as parallax) which happens to all outer planets near opposition: at this time the Earth is "overtaking" them in their journey round the Sun and so relative to the fixed stars they appear to be going backwards. (To find out more about this phenomenon, click here) |  |

This is a highly expanded version of one of the images of Uranus, showing that the planet is coloured blue-green (which is indeed true!). However, don't be deceived into thinking that the circle shown here actually represents the disc of the planet - this (at 3.7 arc-seconds, or just 1/1000 of a degree!) is only just resolvable with the telescope [as shown by the first images on this page]. Uranus, and indeed all the stars, should be just a point of light - the camera spreads the images into small circles due to the exposure times required, the fact that its focus isn't perfect at this scale and probably by the action of the digital zoom. In this case though, a green blur is definitely more convincing than a tiny green spot! This is a highly expanded version of one of the images of Uranus, showing that the planet is coloured blue-green (which is indeed true!). However, don't be deceived into thinking that the circle shown here actually represents the disc of the planet - this (at 3.7 arc-seconds, or just 1/1000 of a degree!) is only just resolvable with the telescope [as shown by the first images on this page]. Uranus, and indeed all the stars, should be just a point of light - the camera spreads the images into small circles due to the exposure times required, the fact that its focus isn't perfect at this scale and probably by the action of the digital zoom. In this case though, a green blur is definitely more convincing than a tiny green spot! | |

I was highly delighted to get these shots of Neptune as I had always thought I would never be able to see it - thank heaven (literally!) for two very clear nights. When I realised I had indeed captured a good image it really made my day. [And just in case you're wondering - no, I shan't now be trying for Pluto: it never gets above magnitude 13!!]

|  |

| As with Uranus, first find your target! Neptune is the middle one of the three at the bottom. None of the stars is bright enough to be named, the brightest being only about magnitude 7. Because of this, the exposure had to be much greater than for the location shot of Uranus, thus turning the stars into "trails" rather than blobs. | Four days later (i.e on 14th September), Neptune had moved quite noticeably. The scale of these images is different from those of Uranus: calculation shows that Neptune has actually moved just over half as far as Uranus in the four days. |

|  |

| And just in case you're in any doubt, here's the modern digital equivalent of the old "blink comparator" showing it actually moving. This is how Pluto and many asteroids were discovered - comparison of two photos taken some days apart. | This highly expanded version of one of the Neptune "trails" shows that the colour of the planet is quite different from Uranus - light blue. It also shows that the Earth's atmosphere wasn't entirely steady during the exposure, causing a considerable variation along the trail. |

As I mentioned above, the major problem with photographing the outer planets is finding them in the first place. I was thus pleased to find that in late 2008 Venus would be moving very close to Neptune and would thus provide an excellent guide to that planet's position. The two were at closest approach on 27th December, and I managed to capture images of Neptune on 26th, 27th, 29th and 30th December (cloudy on 28th). These were of variable quality, so needed a fair amount of digital processing, but the end result was most satisfactory.

|  |

| On 26th December, Venus was just below Neptune, looking distinctly like a comet due to the degree of over-exposure necessary to capture the outer planet: it's the middle one of the line of three at top right. All the stars are in the constellation Capricorn but except for Nashira (bottom left) none is bright enough to be named, being only about magnitude 5 or 6 at best. Neptune itself is magnitude 8. | Just one day later Venus had moved very noticeably but Neptune had also moved, though you might need to look carefully to persuade yourself of this! This is the point they were at minimum separation: 11/3 degree. |

| It was cloudy on 28th but I was able to capture images on 29th and 30th. Venus had move out of shot by this time but not so far away that I couldn't use it as a reference. This montage makes Neptune's movement very clear, and also shows the gap from the "missing" image on the 28th. Comparison with the above images shows that Neptune's track is "up and left", which is in the opposite direction to that shown previously for both Uranus and Neptune. The reason for this is straightforward: the planet was well past opposition (on 15th August) and so was moving in its "correct" sense relative to the stars at this time. |

In early January 2017 I noted that Neptune was very close to Mars but when I tried to get some pictures I discovered that the camera I had purchased to replace the original one (which had developed a fault with its lens) didn't seem to be focusing properly at infinity - well it did only cost me £35! It took a while to confirm this, by which time Mars had moved away. Conveniently however, Venus stepped into the breach and so after several days of bad weather I was ready to try again. The fault with the first camera was intermittent, so I was able to get a few shots on 14th January which I was able to stack together to give a very satisfactory result, shown here:-

|

Neptune is the bluish "star" to bottom centre with (fairly obviously!) Venus to top left. The strange blob immediately under Venus is not an artefact of the imaging process but is actually the magnitude 3.7 star Lambda Aquarii, which just happened to be a mere 8 minutes of arc away from Venus! The other stars are not bright enough to be named, the brightest (at bottom right) being mag. 6.4 and those running up above Neptune mag. 7 or 8: Neptune itself is at mag. 7.9 for comparison. I had originally intended not to take any more pictures, but a clear sky on 19th January enticed me out with the camera I'm afraid! Click or tap on the image to see Neptune move quite considerably between these two dates (which at least shows I'd got the right target!). Venus had disappeared off to top left by then, allowing Lambda Aquarii to be seen in all its glory. Another click/tap will take you back to the original position. |

I had much earlier realised that the appearance of Venus high in the south-west at the turn of the year was a good example of the well-known 8-year recurrence relationship in its position, 13 Venusian years being almost exactly equal to 8 Earth years. Having confirmed this with my planetarium program, it then occurred to me that the Venus-Neptune conjunction might also have repeated. By experiment, I found that the situation on 14th January 2017, as shown above, was almost exactly the same as on 28th December 2008 (the "missing" date from the previous conjunction): the separations were the same to within half an arc-second! (at 1deg 54sec). This interval between these dates is 17 days greater than 8 years because the motion of Neptune along its 164 year orbit took it away (to the east) from the original conjunction point. In 8 years it would travel 171/2 degrees, which would take the Earth just 173/4 days to cover. This would, to a reasonable approximation given the distance of Neptune from the Earth, restore the conjunction position if Venus were stationary but of course it also is moving. However, because Venus was approaching greatest eastern elongation at this time and so would have been travelling almost directly towards the Earth, its orbital motion had only a small effect. What effect there was would have been in an "away from the Sun" direction as seen from the Earth, which would move Venus nearer to Neptune in the sky, thus reducing the time to restore the conjunction position, as found. A satisfying agreement between observation and calculation!

While I normally keep track of the position of the brighter planets, I don't normally bother with Uranus and Neptune as they are hard to find and therefore to photograph. I was thus surprised to find that Jupiter and Neptune were very close together on a star map I was consulting to determine the track of a pass of the ISS. Not wishing to overlook a possibility of capturing Neptune I thus took a sequence of shots at the highest magnification (the equivalent of an 800mm focal length!) and was pleased to find that the outermost planet was nicely visible. Another sequence a couple of days later enabled me to show the movement of Neptune (and of course Jupiter), to confirm I had captured it. Combining several shots into one greatly improved the final images, even bringing out Neptune's distinctive light-blue colour.

|  |

| On 12th July 2009 Jupiter was just past its closest approach to Neptune but even so the separation was only a fraction over 1/2 degree, which makes it a very close conjunction. Neptune is to the top of the image, with the 5th magnitude star Mu Capricorni between it and Jupiter with its satellites Ganymede, Europa and Callisto. | A couple of days later Jupiter has moved appreciably (as have its moons) but the motion of Neptune is also clear. Note that both planets have moved left-to-right: this shows they must be near to opposition (the "normal" motion is right-to-left). In fact, Jupiter came to opposition on 15th August and Neptune on the 18th: Neptune was also at its nearest point to the Sun at the same time which meant it was at its very brightest - still pretty dim, though! |

| The date when Neptune came to opposition coincided with several days of very clear nights here, so I felt I should not miss the opportunity presented! I was able to capture the outermost planet on six consecutive evenings (from 18th to 23rd August) and thus produce a good composite image showing its motion very well. And yes, I did say six observations. The left-most blob is not a mis-aligned seventh observation but a magnitude 8.6 star, which Neptune almost occulted on the 17th - just 40 arc-seconds away! Neptune was at magnitude 7.8, appreciably brighter than most of the stars around it. The three exceptions include (at left) Mu Capricorni, as shown in the images above [note that by this time Neptune had moved a long way to the west i.e. right and that Jupiter was way out of frame to bottom right]. It's perhaps just as well that cloud did begin to gather on the 24th as that gave me a good excuse to stop taking pictures. Capturing the raw images is relatively easy - processing them into a composite image is the bit that takes the time! This one is made up of 24 separate images, selected from many more. Those taken on each evening were rotated & aligned and then combined together to enhance the detail while cancelling out the "noise". The six intermediate images thus produced were then themselves adjusted and balanced before being brought together to create the final result. |  |

| As mentioned above, Uranus was in close conjunction with Jupiter on 21st September 2010, when both planets were simultaneously at opposition and perihelion. I thought I should commemorate this unusual event with a suitable image, though intermittently cloudy weather prevented me doing anything in the way of a montage over several days. So, here we have Jupiter at the bottom of the frame with (from the left) its moons Europa, Io, Ganymede & Callisto in close attendance. Uranus is at the top of the frame, immediately above Jupiter, showing its characteristic slight green tint. The separation was 50arc-minutes (0.8deg). |